Home Is Where the Horrifying Tacos Are

Culture is healing, vegan Mexican-Americans who eat plant-based al pastor know this.

Tacos from Por Siempre Vegan, Ciudad Mexico, 2019.

My boyfriend makes fun of me when people ask where I lived in Tijuana. To say I’m bad with directions, is an understatement, I’m utterly hopeless. We left Mexico when I was seven, and I lived there again for a while at thirteen, before we moved to Texas for a year. So when people ask, I’d just say “por el Tacomiendo.” That was my compass and reference point––my neighborhood taco joint. El Tacomiendo was a little yellow and green taco stand that punctuated the end of the steep downhill street we lived on––the name is a play on words meaning, “they’re eating.” The names of the many other taco shops we visited, where I’d gorge on al pastor, carne asada or de pollo with marvel, have faded away with the passing of time. We visited many often––much more religiously than church, and the feeling always the same, that of home.

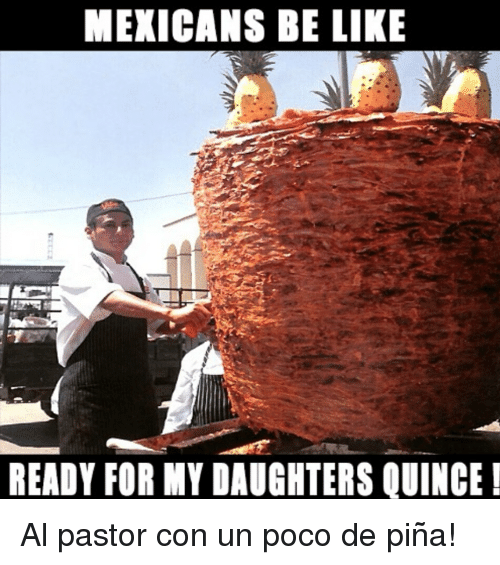

My hunger for tacos was what would ultimately keep me from going vegetarian at an early age, the reaction from friends being that a Mexican person could never go without meat. Meat was central and definitive of our culture, apparently. So I’d try to be vegetarian, against my parent’s wishes during the week in San Diego, and then when we’d visit Tijuana on the weekends, I’d break and have a taco. Al pastor and carne asada were my favorite. Visiting a taco stand was a ritual replete with nostalgia, tradition, and excitement. It was an education and source of entertainment watching the meat being chiseled off the trompo, landing softly onto a tortilla de maiz, meat chopping on a butcher’s block, toppings flying faster than you could keep track. I’d cross the border back with a belly full of al pastor, weighing my conscience, wondering if maybe the nay-sayers were right, maybe Mexicans couldn’t be vegetarian.

I remember my dad’s friend Chucho, once telling me that his friend got really sick as a vegetarian, surviving only on flour tortillas. As if to say, nothing except our tortillas are vegetarian in the Mexican diet.

But of course, if his anecdote was even true, his friend was forgetting about everything you could stuff into a tortilla, like beans, corn, rice, squash. He was forgetting tacos de huitlacoche and tlacoyos de frijol, about burritos de frijol con queso fresco, chiles rellenos, arroz rojo, frijol a la olla, chilaquiles, molletes, and so much more. He was forgetting how richly plant-based our foods were pre-colonially, and how much we still rely on them post-colonially.

Even then, with so many vegetable-forward meals, there is still such a strong aversion towards vegan Mexican food, by both Mexican and non-Mexican people. One that has survived my early attempts at vegetarianism and successes from middle school to high school (I was vegetarian for six years pre-veganism), to my fourth year of being vegan at twenty-nine going on thirty.

image source

Even if I don’t like it or agree with it, I can understand the disdain towards recipes that replace and substitute, and ultimately modify traditional dishes from Mexican people in the United States. I understand the desire to preserve and protect. Food is a tangible connection to a culture whose heart beats in another country. But when will our own community understand that Mexican vegans––who have chosen to cut out meat and dairy for reasons that are either political or health-related (or both!), existing within a subculture that centers whiteness––are only trying to do exactly that? Preserve. Survive. Connect.

What I can’t understand, however, is why non-Mexican people––like a certain critic who took to twitter late February, calling a vegetable-based trompo “horrifying”–– are comfortable being an authority on what’s Mexican. Is it horrifying because it doesn’t have pig parts? And therefore, because it lacks pig parts, is it not Mexican enough to be al pastor? I would sooner call the living conditions of the pigs set to slaughter horrifying before I deemed someone’s chance at reliving a treasured and cultural experience lost to time, politics, ethics, or illness, horrifying.

When I first moved to New York, I had been vegan for about a year. I was living on the border of Lower East Side and Chinatown, Chinese and vegan food galore. It was heaven. Until one day, it hit me like a ton of bricks. I hadn’t heard anyone speaking Spanish around me, or seen any fruterias that sold tortas, or any spots with good burritos. It was an emptiness that I could only fill by visiting JaJaJa, a plant-based vegan spot near my apartment, as often as I could afford (and thank god for them!). Then suddenly, after some health complications––my dad is a diabetic, and I am a hypochondriac with gastritis, so I’m on alert––I put myself on a strict diet. I was eating salads daily, putting greens into everything, even my smoothies with no fruit or sweetener. It was helping until it wasn’t. (There’s more to be said on this subject, but I’ll save it for another time.) You see at that time, I began studying to be a health coach and my mission was to learn to use food as medicine. At some point in the program, we began exploring what primary and secondary foods are. Primary foods being relationships, physical activity, career, etc. Secondary foods being what we actually cook and eat. The idea in post-modern nutrition is that you are nourishing yourself with both. I realized that perhaps what I was missing in order to truly heal was an essential primary food: my Mexican culture.

It was then I began fueling all my energy towards veganizing foods I loved as a child, foods I cherished but never knew how to make. It was only then I began to develop a true affinity for connecting with my culture, through music, language, art, history, and most importantly and tangibly, food. I was living proof of the adage, you never know what you have until it's gone.

Going vegan in a non-vegan household, in a culture that presently centers meat and dairy, means being on the fringes––on the outside looking in. When I first went vegetarian, at age fifteen, I had to learn how to cook, my mom wasn’t going to cater to me––no es restaurante, she would say. So I learned to cook rice, squash, and beans, haphazardly, eating a multitude of quesadillas and veggie burgers in between. Even then, I could still go eat a quesataco de huitlacoche or a bean and cheese burrito and have a taco shop experience, if I wanted to.

In fact, it was at a taco shop late one night, where I’d usually get my bean and cheese burritos in the wee hours, where I first met my boyfriend.

Being vegan, however, presents its own nuanced experience and limitations. Eating out and participating in our cultural traditions proved difficult. I didn’t eat rosca on Dia de Los Reyes, or tamales on Christmas because they’d have cheese if they didn’t already have lard. Of course, access to vegan versions of this has boomed in Southern California since then––part of the reason I’m here now.

It wasn’t up until April of 2019, that I had tacos the way I used to since going vegan, at Por Siempre Vegan in Ciudad Mexico. The excitement of being able to eat al pastor again, street-side on a sidewalk engulfed me. I felt I belonged.

Eating tacos at Por Siempre Vegan, April 2019, shot by my dad.

The same feeling crept up again a couple of weeks ago when I visited Evil Cooks––a pop-up taco shop with an omnivorous menu and the internet-famous vegan al pastor. Watching it cook, stacked in all its vegetable glory, pierced through with the trompo I knew and loved growing up, filled me with unimaginable joy. These are my small pleasures, not only in the middle of a pandemic but as a vegan Mexican-American with broken Spanish who doesn’t seem to belong anywhere. It is in these rare moments, standing in front of a taco shop with a vegan al pastor on a spinning top that I feel part of something.

Like my existence is acknowledged and welcomed.

Especially in a country that would rather I not be here, to begin with.

Maybe that’s what the al pastor has signified all along: a sense of belonging.

The taco’s history itself, with its Lebanese roots, is a vivid reminder of resilience and acclimation through culinary tradition. Lebanese migrants adapted a recipe from home to a new country by swapping lamb for pork, and pita for tortilla, forging a new dish called “al pastor” out of shawarma––creating a dish so delicious and beloved, that it literally became a national symbol for Mexicanness.

image source

So perhaps too, like the pork al pastor, the survival of our culture––for vegan and vegetarian Mexican-Americans like myself––can be given the grace to adapt and be preserved in something as delicious and “horrifying” as a trompo al pastor made with layers of mushrooms and eggplant. So that we may enjoy a relic from many tacos past, while crossing cultural, lingual, and federal borders, to give us a taste of what we’ve left behind: a taste of home.

Thanks for sharing this.