Still with Life

A meditation on still life fruit paintings and what they bring to today's table.

*Author’s note: Arriving a day late to your inbox, but better late than never, right? Thank you for your patience and continued support!

In this newsletter you will find some beautiful fruit still lifes, they have been curated by my good friend, Daniel Ivan Leyva-Peterson, art-aficionado, Art History Graduate, and Art History Masters student at CUNY. Think of it as an online gallery.

Please enjoy.

-

As a young girl, art came easy to me. My parents, in an effort to nourish that, signed me up to take various art classes, sometimes of portraiture with pencil, or simply still lifes of flowers or paintings with oil, watercolor, or acrylic paint. When we moved to the states, I was enrolled at Miss Jessica’s Bonita Art School in San Diego, CA––and she was the real deal. I wound up taking them for about six years, before we moved to Texas, and then sporadically for a little when we moved back.

I could not produce any photos of my artwork as a kid for this piece at this time (but this is where they would go!)

Jessica Symond’s class was broken up into two parts: the first was a drawing exercise, usually with charcoal or pastels, and usually a still life. Her own still lifes of oil fruit paintings hung around us, pomegranates were the main star and if memory serves me correctly, she had some trees in her backyard––pomegranate trees grow in San Diego, along with a few other varieties. Sometimes we’d draw a collection of objects from around the studio, like paint tubes, flowers in vases, or shoes. Sometimes we’d have someone from the class volunteer to sit, then we’d all sit around as a class and critique our work. My favorite, and I think hers too, was when she’d bring fruit to class for us to draw. She found such joy and importance in teaching us to appreciate the depth of capturing fruit. Plus, we’d cut it up and eat it afterward. Miss Jessica would turn on her CD stereo and blast Mozart, or Cher, or the Beatles, zinging us little artists with a surge of sunny energy on sleepy Saturday mornings. The studio smelled like turpentine, the carpets boasted dashes of dried-up oil paint, rugged from the wear and tear. We all wore extra-large used shirts covered in streaks of oil paint instead of aprons, in the name of sustainability (she was ahead of her times). Miss Jessica grew up in Mexico and in the United States, she embraced the two worlds with ease and grace. I can’t express how much her guidance served me, as I treaded a new world stark in duality. She saw me, even as a child, and gave me such respect as a person.

During our still life practice, she’d emphasize to draw what we saw. She’d explain that often people make the mistake of drawing things the way they think they should look, but the trick to accurate replication is to actually see your subject. Perhaps this translated to how she saw people, clear and accepting. This was empowering to experience. I still remember her voice as I write this, “draw what you see, not the idea of it,” and it’s never left me. Even a decade after she’s left this earth.

Pomegranate , U.S. Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection. Rare and Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, Beltsville, Maryland. Provided by Leyva-Peterson.

Anyone who took her class painted a fruit still life as their first, this was foundational work, the predecessor to any and every other painting you would produce henceforth.

The painting, and study of oil, was done in the second half of class, after the snack break to the liquor store around the corner. Completing a painting would take months of work, each its own lesson in art theory, technique, and practice. It was also an opportunity to develop personal style.

Naturaleza Muerta con Limones, Diego Reivera, 1916

Still lifes then, as an artist; were a foundation, a prerequisite, a practice, something to master and come back to, over and over.

Still lifes now, as a viewer, in a moment of so much uncertainty, of so much pause, and hurt and pain, have yielded a different effect: they’ve been a balm to my soul, beauty in ugliness, stillness in chaos.

Three peaches on a stone ledge with a Painted Lady butterfly, oil on paper, Adriaen Coorte, 1693-1695, provided by Leyva-Peterson.

I find myself rejoicing, quietly, at the sight of one while scrolling Instagram or flipping pages of art books. Amidst all the chaos, inside a little square picture of exquisite fruits, there’s a calm. They're a peek into a moment in time of another ripeness of life. They’re an escape to stillness, acute presence, and wonder. Because you see, a still life is exactly that: life in stillness. Life in study. And so it is a respite amongst turmoil, to find those moments in our day-to-day where one’s soul can be at ease if only for a moment, in admiration of beauty and wonder. To reflect on earthbound majesty, abundance, mystery, and history.

The scene is one of beauty, fruit itself is beauty. It is an artistic expression in nature, juicy jewels of the earth fruiting from trees and shrubs to nourish us. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in his book ‘Nature’, that we behold beauty in the natural world because in of itself, its “outline, color, motion, and grouping,” is beautiful. “The eye is the best of artists.”

Adriaen Coorte, Still Life with Asparagus, Oil paint, Panel painting, 1697. Provided by Levya-Peterson.

These scenes too are laced with an air of mystery and a sense of imagination. Where did these fruits come from? Who picked them? Who’s eating them? What’s outside the frame? What season is it? Whose home is this? Who sits on that table, or peers out that window? What is the life surrounding this image?

The still life itself reveals some answers, but its composition still leaves endless possibilities to the imagination. It’s a mad lib to improvise on, leaving blank spaces for the viewer to be spirited away into a fictionalized world when the present can feel unbearable. Their depth of color, in myriad hues and shades, with variations both familiar and foreign–––telling a story all on their own, a story of foodways, history, and class, culture, and even plant genetics.

Still life with fruit, Bijan Ghaderi, Persia Mid-19th Century, Oil on canvas. Provided by Levya-Peterson.

These paintings have the capacity to pinpoint and immortalize precise moments, environments, times in history, even seasons, with the immense beauty that is mother nature front and center. Fruit still life paintings alone have documented so much of our evolution with crops, in fact, that plant geneticist Ive de Smet and art historian David Vergauwen embarked on a research project last summer that utilizes fruit still-lifes as blueprints that trace back how much fruit has evolved over centuries.

They’re marrying the study of “modern plant genetics with centuries of still-life paintings” in order to “create a visual timeline of produce domestication.”

A study of Flemish Baroque painter, Frans Snyders’ paintings triggered this research project when they thought Synders lacked the talent to paint fruit. When they realized that perhaps it wasn’t so much that Snyders lacked the talent to reproduce pictures of fruits, but more so that the fruit itself may have looked differently in the 17th century, a lightbulb went off.

Strawberries with a Carnation, oil on panel, Frank Snyder, 1579-1657

Still lifes have told the story of carrots, who started off as weeds, strawberries that once looked to be as small as raspberries, and of tomatoes who made their grand entrance to Italian art and cuisine after they were plucked from the New World by colonizers.

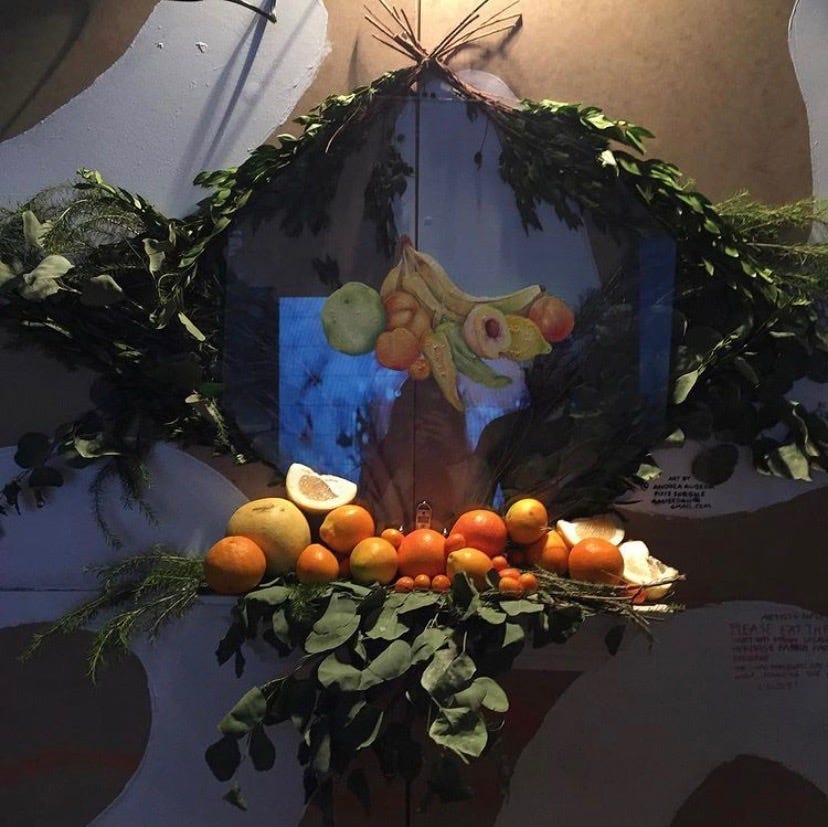

In 2017, I showed at my last art show. It was a still life of yellow fruit, most of it from local farms (with the exception of bananas). The idea was to promote local foodways, to experience the joy and beauty of the fruit that surrounds us. I set up the display with a mound of citrus: grapefruit, kumquats, and oranges––they were free to take. I called it a “scratch and sniff” piece.

Still Life, Oil on glass, Andrea Aliseda, 2017

Visiting the farmer’s markets here in Los Angeles has given new life through which to view fruit and produce. I take home a bounty of citrus, berries, tomatoes, peppers, and it makes me wonder if this was the artist’s relationship to their fruit still lifes. Did they paint the fruit that was around them? Did they think of how the fruit got to their studio? Did they know their farmer?

In the way the world went back to basics by baking bread from scratch at the start of the pandemic, perhaps we too can also find some solace in embracing the natural world and rejoicing in its beauty all-the-while protecting it. Perhaps farmer markets can be a gallery, and our baskets of fruit our work of art. Fruit as we know it, is a ripe marker of our time on earth, of the land we grow on; its flavors, shapes, and colors, a reflection of our climate and how our presence has altered it.

I wonder if people can be more motivated by beauty than by duty. I wonder if the pursuit of preserving our earth’s natural beauty would incentivize the responsibility we have to protect this earth.

Perhaps now––as our planet starves for care––is the perfect time to return to this stillness and appreciation of the art and beauty that surrounds us in the natural world. A time to return to a respect for the trees that exhale oxygen and the fruit that hangs heavy from arched curving branches, waiting to be picked. How important it is to value fruit in its nutritional value, with respect to the laborers behind it, and respect to mother nature’s genius design––perhaps reveling in the thought that it may never exist the same way again.

Perhaps too, still lifes are proof that everything changes, everything grows and transforms. And so maybe in that, there is hope that things can change if we stay still enough to see things are they are.

Anne Vallayer-Coster, Still Life with Marine Plants, Shells & Coral, 1769. Provided by Levya-Peterson.

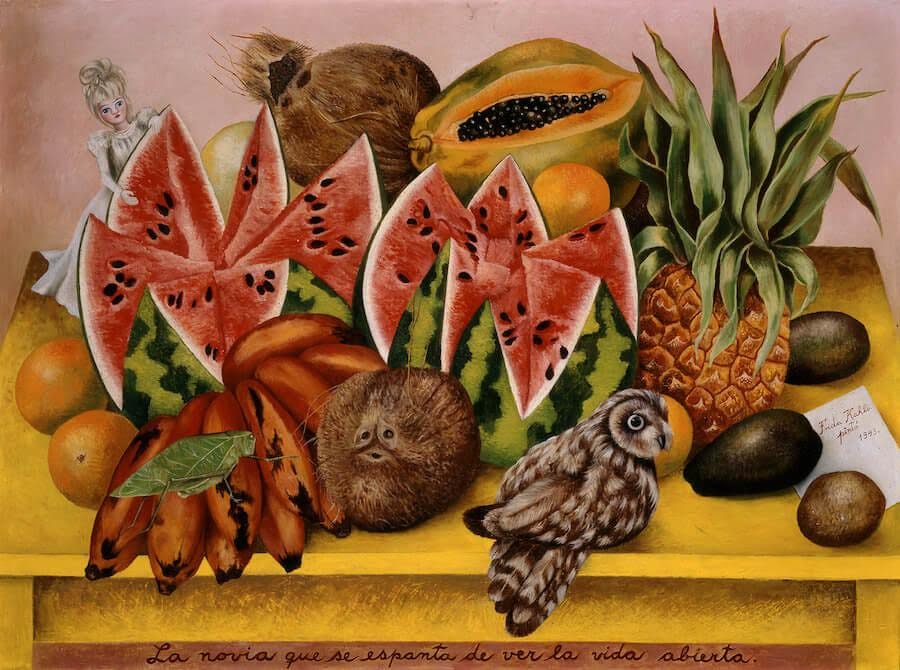

Frida Kahlo, The Bride Frightened at Seeing Life Opened, Oil on canvas, 1943. Provided by Levya-Peterson.

Heinrich Kühn, 1908. Provided by Levya-Peterson.

Joseph Proctor, Still Life with a Basket of Fruit, Flowers and Cornucopia, 1860, Oil on canvas. Provided by Levya-Peterson.

Adriaen Coorte, 1696, Strawberries Mauritshuis. Provided by Levya-Peterson.